Back to Its Roots

The introduction of an “adversity score,” however, undermines the SAT’s recent claims that achievement is important.

In April, Jeremy Singer, the new President of the College Board (the makers of the SAT), stated in a discussion about the introduction of adversity scores that “An SAT score of 1400 in East L.A. is not the same as a 1400 in Greenwhich, Connecticut.” Really? Isn’t the whole point of a standardized test to provide an objective, meaningful score so that students can be compared regardless of context?³

Singer’s meaning, of course, was that a student should be given more credit for the same score if they have a disadvantaged background. Ignoring the fact that the new adversity score imperfectly and discriminatorily measures disadvantage, giving students more credit for a standardized test score depending on their perceived background either means that achievement (as measured by the SAT) is not predictive or relevant for assessing success in college or that colleges should not focus on what will lead to success in college.

Does Achievement Predict Success in College?

But achievement (as measured by the SAT) is moderately predictive of a student’s GPA in college – there is a .37 correlation between SAT scores

Thus, SAT and (probably even more so) ACT scores are decent measures, particularly when combined with high school GPA, of achievement in high school and are predictive of achievement in college. Yet, the SAT has provided no data at all that suggests that the addition of an adversity score improves a college’s ability to predict success in college. The only results-driven data that it has provided are that colleges using the new adversity scores see increases in the underrepresented groups of students that they are targeting.²

Should Colleges Care About Success in College?

That latter question seems ridiculous to ask. One would think the answer would be, “Yes. Of course. Obviously.” But an adversity score questions that assumption. Although I would disagree with the following, I am open to being wrong: maybe colleges should care more about providing equal access to higher education than their students’ success in higher education. Regardless of the value judgment we put on what colleges “should” care about, I think the SAT (and colleges) need to be transparent about what they value. And, I think they need to be honest about the dangers of setting a precedent that the fruits of achievement should be mitigated or even eliminated when balanced against other possible social conditions over which a student had no control.

What the Adversity Score Measures

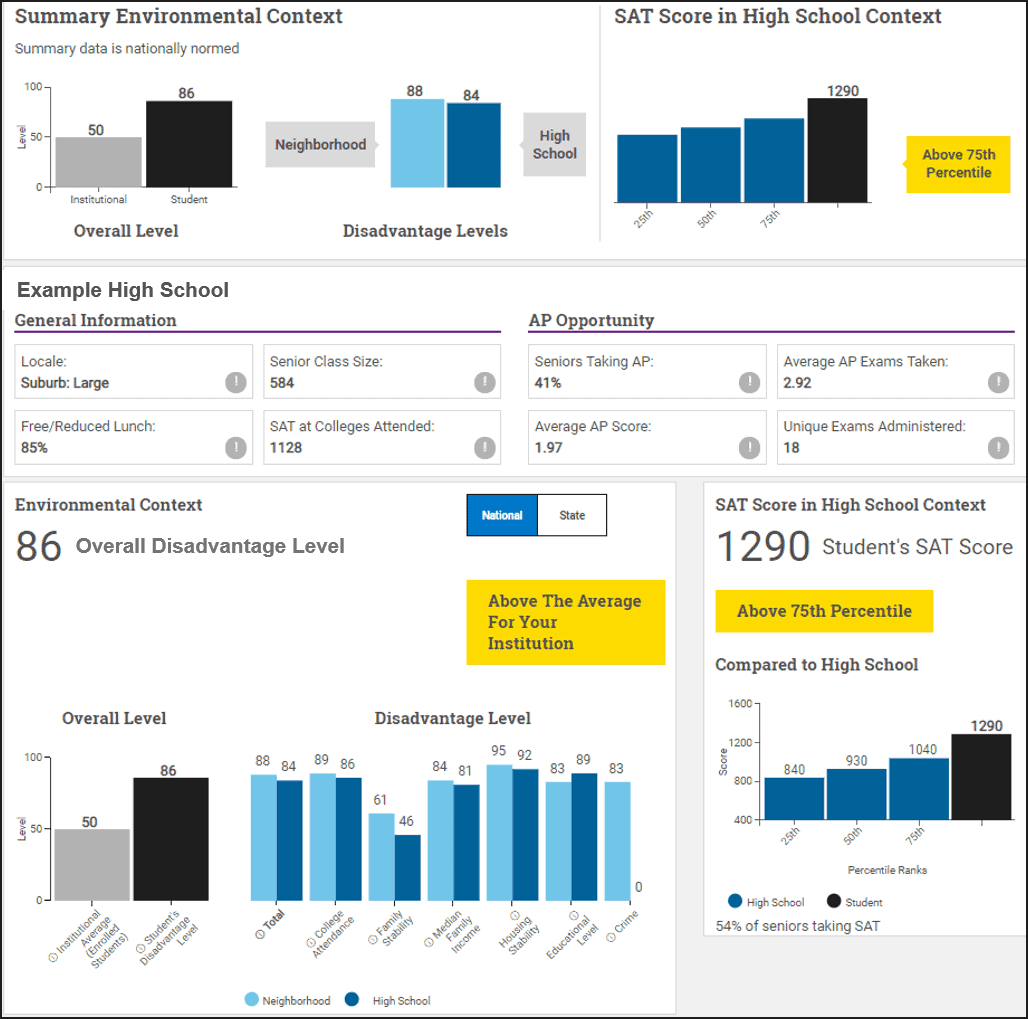

The SAT will provide colleges with an adversity score, ranging from 1-100, that is a composite of 3 broad categories and 12 subsections of a student’s possible adversity. A score of 1 will indicate a student is predicted to have experienced the lowest adversity relative to other students, a score of 50 will indicate a predicted experience of average adversity, and a score of 100 will indicate the highest predicted amount of adversity that a student could potentially face.

Here are the categories and subsections:

-

Neighborhood Environment:

- Crime Rate

- Poverty Rate

- Housing Values

- Vacancy Rate

-

Family Environment:

- Median Income of Families in the Surrounding Community

- Percentage of Single-Parent Households in the Surrounding Community

- Average Educational Level of Adults in the Surrounding Community

- Percentage of Surrounding Community that uses English as a Second Language

-

High School Environment

- Undermatching (whether a student is outperforming other students at their school but underperforming students on a larger scale and, thus, allegedly at risk to be “undermatched” to colleges that are below what they deserve)

- Curriculum Rigor at the Student’s School

- Free Lunch Rate at the Student’s School

- Advanced Placement (AP) Course Opportunity at the Student’s School

Immediately problematic is that the SAT does not disclose all of its sources of data, which it says are proprietary, that it uses to build a student’s adversity score. This secretiveness casts doubt on the validity of its data because there is no way to independently verify the accuracy of their information.

However, even if the data are accurate about a student’s high school and community, that data is still potentially not very relevant or even entirely irrelevant to the individual student. For example, whether a student is from a community with a higher than average percentage of single-parent households and where English is a second language is dramatically less relevant than if the individual student actually is from a single-parent household and if English actually is a second language in the student’s household.

A probability of experiencing adversity is wholly unacceptable when it is applied to individuals as a single composite score. In practice, the probability of experiencing adversity is being supplanted with an assessment that the student did or did not experience adversity. This substitution

For example, what would be the adversity score of the following student? Her parent is a single-mother who immigrated from Vietnam and speaks

Thus, even if a consideration for adversity is worthwhile, an adversity score from the SAT can be incomplete, misleading, or simply wrong. In order to measure adversity and assign student’s a single score, the score needs to be based on that student. If colleges believe they need this information, then they should require it from applicants and not judge individuals on the probability that they faced adversity. With the SAT’s adversity score, what is true becomes less important than what is possible. The individual becomes less important than the group or class to which they might belong.

Secret Judgment

To me, however, potentially the worst aspect of the adversity score is that it will be kept hidden from the student. Doing so is problematic for two reasons: 1) The adversity score might be wholly inaccurate, yet the student will have no idea that they need to address the inaccuracy if they have no way of knowing about it, and 2) The student needs to know their adversity score in order to make informed decisions. For example, if a student

Outcome

We do not have to speculate whether students with low adversity scores are being devalued. Both the SAT and colleges have said that adversity scores increase the number of students admitted with high adversity scores.

I hope that the SAT and colleges see the perils of assigning demographic generalizations to individuals. Yet, the temptation for colleges to use a free and simple adversity score, however imperfect, is likely too appealing to pass up. Sadly, the ACT (which usually caters less to the whims of college admission offices – it lets students delete ACT scores, etc) has also said that it is developing a similar tool that it will announce later this year. (Important update: After this post was published, the ACT’s CEO, Martin Roorda, rebutted prior reports that the ACT would be developing its own adversity score equivalent and instead confirmed that it disagreed with the SAT’s approach — using many of the same objections raised in this article — and would not be providing a similar score to colleges.)

Through diversity scores, a college might (correctly or incorrectly) convince itself that it is opening access to higher education. Yet, doing so will